When you enter a Greek Orthodox church, you’re immediately struck by its mystical atmosphere: a dimly lit interior, dark but multicolored frescoes highlighted with gold, daylight streaming in through the central dome. The spirituality exuded by the flat, almost unreal figures, the false perspective of the landscapes, the absence of shadows, encourages the faithful to escape the earthly world and enter into communion with God. Here are a few keys to understanding Byzantine murals and icons in a Greek church.

The war of images

In 726, Emperor Leo III decided to remove the icon of Christ that adorned the bronze door of his palace in Constantinople. This event marked the start of a long and bloody war between iconoclasts (image breakers) and iconolaters (image worshippers).

The cause? Excessive Christian adoration of icons and relics, which diverted Christians from the faith and brought them closer to the customs of paganism. For over a hundred years, successive emperors either strongly repressed or authorized the worship of icons. All this against a backdrop of Arab and Bulgarian invasions, heresies concerning the nature of Christ and the spread of Islam (with its non-figurative art).

On the island of Naxos, you can still visit chapels from this period (9th century) whose decoration has no human representation: Agia Kiriaki in Apeiranthos or Agios Ioannis Theologos in Adissarou.

Finally, the cult of icons was re-established in 843. Despite the damage, the iconoclastic conflict enabled the Byzantine Empire to assert its political, theological and artistic identity. Wall iconography and portable icons became the main media for Byzantine art and Eastern Christian dogma.

Byzantine icons

Icons, portable paintings of sacred figures, can be found in every Greek church. Two main techniques are used to create them: for the oldest the encaustic paintwhere the dyes are mixed with beeswax and pine resin and then applied hot to the wood to be painted; the temperature where the colorants are diluted in a mixture of egg yolk and vinegar.

Byzantine icons are sometimes adorned with a silver or gold plate, revealing only the saint’s face and hands. It’s a way of protecting fragile colors from light or vandalism, while at the same time making them more precious.

Surrounding the icon are ex-votos, embossed metal plaques depicting a character or body part. In fact, the faithful promise the saint an offering, in exchange for healing the person or limb represented (heart, eyes, legs, bust…).

Where to see beautiful Byzantine icons?

Most of the icons found in churches today are reproductions painted in Byzantine technique. If you want to admire ancient Byzantine icons, here are the best addresses:

- Byzantine Museum of Athens, Leof. Vasilissis Sofias 22 Athens, Mo Evangelismos

- Bénaki Museum, Koumpari 1 Athens, Mo Syntagma

- In Thessalonica: Museum of Byzantine Culture, Leof. Stratou 2, Thessaloniki

- Beautiful ancient Byzantine icons and votive objects are also preserved in monasteries all over the country; for example, fine collections can be seen in the monasteries of Meteora and Mount Athos (note: the area is off-limits to women!).

But icons are not only found in churches. Hung on walls or placed on dressers, they adorn the homes of religious Greeks. Even car mirrors and truck and bus dashboards bear the portrait of the owner’s favorite saint. And, as Greece is not a secular country in the same sense as France, icons are often featured on public buildings.

While the Virgin and Child and Christ Pantocrator are the most common images, icons of St. George slaying the dragon, St. Nicholas the patron saint of sailors and the Crucifixion are Greek favorites.

Buy a Byzantine icon

In fact, an icon is a beautiful and typical object to give as a gift or to treat yourself to as a souvenir of a trip. In Athens, several workshops make them, and you can also buy them in the museum stores mentioned above. Prices vary according to the quality of the icon, so here are a few tips to help you understand what you’re buying.

Byzantine icons are painted on solid wood, using the egg tempera technique (αυγοτέμπερα in Greek). And they’re gilded with 24-carat gold leaf. They always carry a certificate of authenticity. It’s a very time-consuming technique. So, depending on the artist and format, you’ll need to spend a few hundred euros to buy them.

There are some very decent icons, hand-finished in lithography on solid wood. They are then aged to resemble ancient icons. To give you an idea, count around 70-100 euros for a 20×30 format. A certificate of authenticity is also supplied.

At last, you can find much cheaper icons. They are silk-screen printed, paper images glued onto plywood or wood for more modest prices.

Wall iconography

Few Byzantine Christians had access to education. So, church walls and icons functioned like books telling the story of religion in a coded language. Coded but accessible to all.

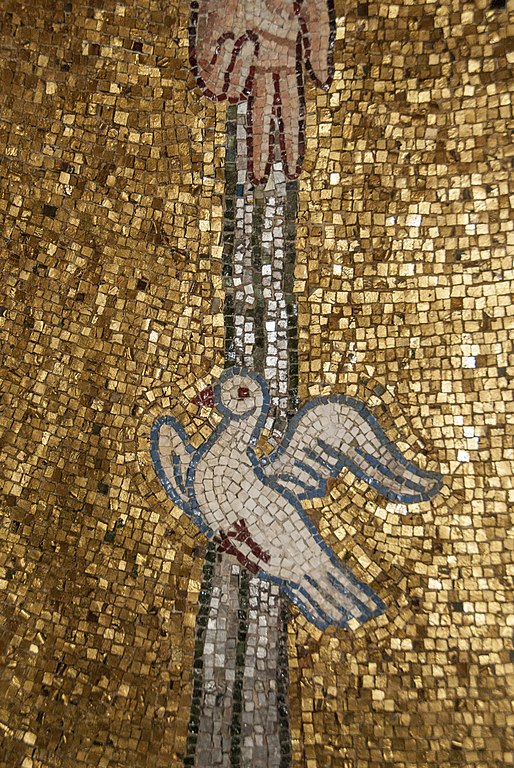

Two main techniques were used to decorate church walls: mosaics and frescoes.

The frescoes have been reworked in most Athenian churches. But you can admire some very old ones at several Byzantine churches as you travel around the country: at Mystrasof Byzantine art, Moni Odigitrias, Moni Périvleptou, Agios Dimitrios; at ThéssaloniqueAgios Nikolaos Orfanos, Panagia Chalkéon; to Patmos the monastery of Agios Ioannis Theologos; in Crete at RethymnoPanagia Myriokéfala…

Magnificent examples of Byzantine mosaics can be seen at Moni Dafniou, near Athens, at Osios Loukas in Boeotia (perhaps combined with a visit to Delphi) and at Nea Moni in Chios; all three are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

In Greek, “icon” means image. After the iconoclastic period, the idea that dominated iconographic production was that of incarnation. In other words, the image is a means through which men can “catch a glimpse” of God.

Orthodox churches

Orthodox churches are designed as symbolic “microcosms “: the designs of the upper part, the dome and apses, represent heaven. The Christ Pantocrator (Almighty) decorating the central dome observes and judges every action. Only angels and prophets can appear and “look” at the divine.

A little lower down, the decoration symbolizes and confirms the Incarnation, the human presence of God among men, realized by Christ. Thus, the scenes described in the Gospels are painted on these intermediate areas.

The lower part bears images of the saints, encouraging the faithful to imitate their lives in order to draw closer to God.

Wall decorations must occupy the entire building. Floral or geometric designs fill the empty spaces. Orthodox churches, on the other hand, have no sculptures, no doubt as a way of distinguishing themselves from pagan antiquity.

Evi S.