Greece’s recent history, from independence to the present day, is often overlooked… And yet everyone knows something or other about the history of ancient Greece!

In schools all over Europe, pupils are lulled by Greek myths, philosophy and tragedies, which, let’s face it, laid the foundations of Western culture.

But few people can claim to know much about Greece’s recent post-independence history. So we thought it might be useful to give you an overview, from independence to the present day.

Greek independence

After almost 4 centuries of Ottoman occupation, Greece claimed its independence in 1821.

This revolution was initially imagined by Greeks in the diaspora, inspired by the ideas of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. It was led by local chefs who were convinced that the idea was feasible, despite the difficulties of organization and equipment.

They weren’t wrong: in 1828, Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first governor of the fledgling country, arrived in Nafplio, which was to become the first Greek capital. Then, with the London Conference in 1832, Greece became an independent, sovereign kingdom under the crown of the Bavarian Otto, or Othon to the Greeks.

National Historical Museum, Athens

Greece’s expansion

As the Ottoman Empire weakened, Greece conquered new territories.

And so the small kingdom, initially comprising the south of mainland Greece, the Peloponnese and the Cyclades, expanded. It gradually incorporated Thessaly (1881), Epirus, Macedonia and the northern Aegean islands, as well as Crete (1913). In 1864, England ceded the Ionian Islands.

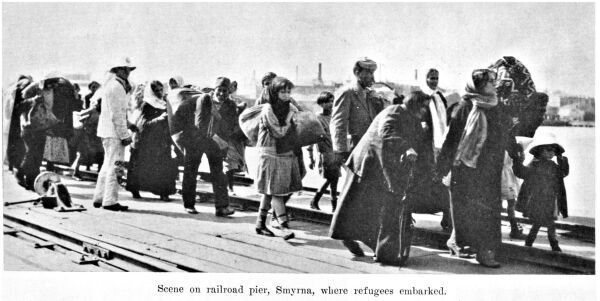

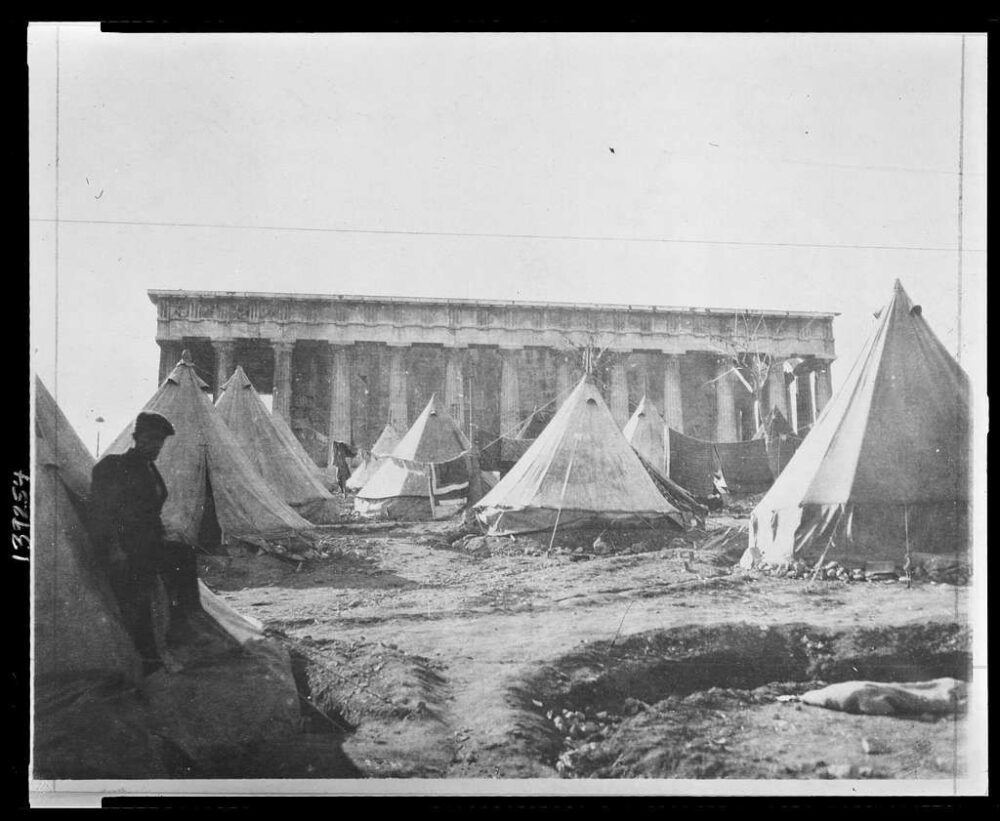

Later, the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the Greco-Turkish Warof 1919-1922 further altered the country’s borders. Following this last war, an exchange of populations took place and 1.3 million refugees from Asia Minor arrived in Greece. This is one of the most painful moments in Greece’s recent history.

Little-known fact: it was the Dodecanese islands, ceded to Greece by Italy in 1947, that completed the design of the Greek map.

Post-war turmoil

The Second World War was followed by a civil war that pitted the government army against the Greek Democratic Army, mainly controlled by the Communist Party.

This war, whose traces are still perceptible in today’s society, lasted from 1946 to 1949. It cost the lives of over 150,000 people. The war left the country devastated, both economically and morally, and drove thousands of Greeks to emigrate.

The huge rift of the civil war has poisoned the country’s political life for a long time to come. Conservative governments followed, entangled in the logic of the Cold War. All they did was perpetuate the divide by persecuting their opponents, often former resistance fighters.

The ’60s were marked by protests, demonstrations and changes of government in the context of a fragile, unjust democracy.

Suggested reading: The book “Z” by Vassilis Vassilikos describes the political and social atmosphere of the period before the military junta, through the story of the assassination of MP Grigoris Lambrakis.

The dictatorship of the colonels

April 21, 1967 is the blackest date in Greece’s recent history.

That morning, the astonished Greeks saw tanks marching through the streets of Athens. Leading politicians were arrested, the constitution was suspended and military songs were broadcast on radio and television.

In his first public appearances, putschist Colonel George Papadopoulos was in a nationalist, anti-communistfrenzy. He compares the country to a patient in the operating room who risks death without urgent intervention and the application of a plaster cast.

Thus plastered, the country will live for 7 years!

Opponents are exiled, tortured and persecuted. To avoid the regime’s abuse, several intellectuals fled abroad, where they made the voice of a gagged Greece heard.

Funerals of personalities such as former prime minister Georges Papandreou in 1968 or the nobelist poet Georges Séféris in 1971 were transformed into demonstrations against the junta.

The Polytechnique insurrection

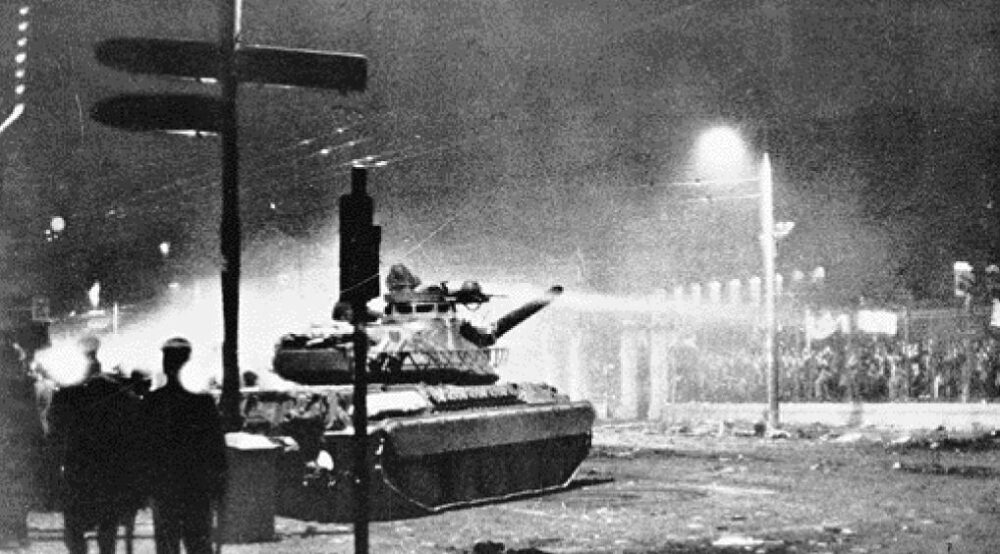

The highlight of the resistance against the colonels’ regime was the student uprising in November 1973.

Despite the promise of elections and the easing of censorship, repression is still the order of the day. Compulsory conscription of “rebel elements” provoked the anger of students at the Faculty of Law, then at the École Polytechnique. They refused to attend classes to protest against the barbarity of the state.

Students and civiliansbegan to flock to the École Polytechnique. The occupation was organized: meals were distributed and an illegal radio station broadcast student messages. The premises are occupied for 3 days.

On the night of November 17, a tank demolished the central gate and rolled into the École Polytechnique courtyard. Televisions around the world will broadcast with horror the images of students clinging to the fence and the voice on free radio begging soldiers not to kill unarmed civilians.

The return of democracy

Following these events, the junta tried to tighten the screws by imposing stricter rules. But his days are numbered!

In July 1974, the Greek colonels instigated a coup d’état in Cyprus. Turkey seized the opportunity to invade the north of the island. Although war between Greece and Turkey was averted in extremis, the crisis put an end to the Greek military junta.

July 24, 1974, Konstantinos Karamanlis returned from Paris and took over as Prime Minister of a provisional government. He then began the transition from military dictatorship to a democratic regime, releasing all exiles and political prisoners, abolishing censorship and legalizing the Communist Party. The first democratic Greek elections were held in November 74.

In December of the same year, a referendum abolished royalty once and for all. In early 1975, a ruling condemned those responsible for the coup and the torturers. Some of them, including Georges Papadopoulos, died in prison.

In Greece, this period of regime transition is called“Metapolitefsi“.

The period of prosperity: 1974-2010

In fact, the Greek “thirty glorious years” began after 1974 and especially after the ’80s. But the country still has some catching up to do. Institutions need to be rebuilt on modern foundations.

Numerous projects were then undertaken, such as civil marriage, the national healthcare system, civil service competitive examinations, major public works, the road network, gender parity, etc.

The country joined the European Union in 1981, completely changing its economic and social foundations. In 2002, Greece entered the big league by abandoning the drachma for the euro. In 2004, it organized the prestigious Olympic Games…

Nothing seems to stop the meteoric rise of this small country…

The debt crisis

But the economic crisis of 2008 revealed the weaknesses of the Greek economy! In fact, the country has long been living beyond its means. But our European partners are turning a blind eye to this dynamic, largely importing market.

In 2010, Greece could no longer borrow on the financial markets and turned to the EU for help. The answer is ambiguous.

On the one hand, the EU cannot let Greece down, at the risk of seeing a domino of eurozone countries go bankrupt.

On the other hand, European experts are implementing a punitive policy for the “bad pupil”. Known as the Troika, this body brings together experts from the European Commission, the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and the ECB (European Central Bank).

As the Greeks saw their purchasing power plummet, they demonstrated, resisted and voted against the unjust memorandums… Governments and coalitions come and go. This tug-of-war with the EU will last 8 long years.

Greece will succeed in staying in the euro zone, and also in cleaning up its operating methods. But it will be another painful moment in Greece’s recent history.

The years of innocence are long gone…

Article written by Evi S.

We recommend reading Victoria Hislop’s novel “Those we love”, which gives a good account of life in Greece during those years.